Arrived back last night from this year’s Geomedia Conference in Karlstad. Three plane journeys and nearly 12 hours from door to door made the return journey quite a slog. Next time I’ll make sure to explore other travel options.

Arrived back last night from this year’s Geomedia Conference in Karlstad. Three plane journeys and nearly 12 hours from door to door made the return journey quite a slog. Next time I’ll make sure to explore other travel options.

Anyway, the conference theme was ‘Revisiting the Home’ and my contribution was as part of a plenary panel (‘Dreaming of Home: Film and Imaginary Territories of the Real’) organised by John Lynch. The other contributors were Nilgun Bayraktar (California College of the Arts) and the filmmaker Christine Molloy (Desparate Optimists).

The plenary session was filmed and will shortly be available via the conference website (http://geomedia.se/conference/2019/), along with a podcast that I recorded with John which will be available here.

The plenary paper I presented was called ‘Homing in Through Film: Movement, Embodiment, Dwellspace‘. Below is the abstract:

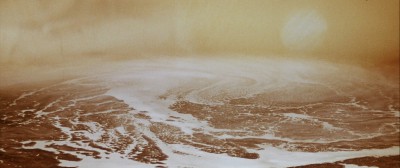

In this paper I set out to explore a phenomenology of ‘home’ that proceeds from contemplative reflection on three scenes from three very different films. In their own particular way, each of these scenes provide an oblique framing on ideas and affects that I am putting under the conceptual umbrella of ‘dwellspace’. Firstly, via Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (USSR, 1971), we consider home as an ‘island of memory’. In this reckoning, home serves as a transcendental u-topos of memory which corresponds with Henri Lefebvre’s (1991) idea of ‘absolute space’. That is, it marks out a sacred zone of authentic being which is phenomenologically rent from the embodied self situated in the here and now of social space-time. It is a ‘heterotopia’ (Foucault 1986) of home that can only exist outside of space and time, but which, like the cinematic image itself, can be accessed through our stepping in to virtual worlds. Secondly, taking as its example the euthanasia scene from Richard Fleischer’s dystopian thriller, Soylent Green (US, 1973), we consider home ‘as a journey to the other shore’, a metaphor, commonly associated with Buddhism, which refers to the journey of transition between life and death (or the afterlife). In this example, home is a place to ‘go back to’ in the sense of securing a locus of eternal dwelling where the transcendence of nature absorbs the soon-to-be-deceased back into its nurturing (or not-so-nurturing) fold. As with Solaris’s home as an island of memory, home in this example is a place that can only be embraced by correspondingly stepping away from the world: home as stasis and death as opposed to an affect of dwelling from where life and movement continue to flow. Lastly, drawing on Hirokazu Koreeda’s After Life (Japan, 1998), I sketch out the contours of a phenomenologically different affect of home: home as a ‘good place’ (eu-topia) of memory. Paradoxically, although the film centres on the activities of the recently deceased (who are being processed through a transitional space – a kind of metaphysical holding area or celestial or purgatorial waystation – en route to an eternity in the afterlife), the idea – or dwellspace – of home that is crafted for those passing through is curiously life-affirming. The paper ends by extending this idea to consider what home might look and feel like as part of a creative spatial praxis: a creative ‘at-homeness’ which connotes not so much a stepping away from the space-time of everyday life, but rather a deep and poetic immersion within it.