On 13 November 2013 as part of the Engage@Liverpool Transformative Legacies series I gave a paper titled ‘Spatial Anthropology: Outline of a Field of Practice’. The event was nominally based around the legacy of the James Frazer who for a short time was based at the University of Liverpool. Other speakers included Ciara Kierans and Bruce Routledge.

The text of the paper I presented is copied below:

Spatial Anthropology: Outline of a Field of Practice

In this presentation I want to follow several threads of discussion that each feed into a broader focus of analysis which is: anthropology as a field of practice. The spatial anthropology bit I’ll come onto a bit later. Framing things in terms of an ‘outline of a field of practice’ obviously has a certain Bourdieuian ring to it, and that is not entirely coincidental. It is also the sub-title of a paper I recently co-authored with Hazel Andrews on tourism anthropology some of which I’ll be drawing on here. As with the arguments put forward in that paper, the rationale for discussing anthropology as a field of practice is to situate what anthropology is (or isn’t) in an explicitly post-disciplinary contextual framework. Those of us here who would readily apply or relate the term ‘anthropology’ to their own practice probably do so in the recognition that we increasingly inhabit and move within spaces that do not neatly align along disciplinary lines, and that, as such, what might count as ‘anthropological’ perspectives sit alongside a whole host of others, some complimentary, others perhaps less so. Up to a point this is of course true for any academic discipline. But one of the questions we might wish to take from this is what happens to anthropology and anthropologists when it – and they – migrate out of anthropology departments? What happens when the field of practice is muddied with the boots of cross- and post-disciplinary intellectual traffic? Or, to put the question in unabashedly Bourdieuian terms, what is the habitus of post-disciplinary anthropology? One way of beginning to address these questions is, in good old anthropological fashion, to reflexively observe or draw from our own ‘anthropological practice’. So in part at least this is what I will try and do in this presentation. I’ll also be exploring more closely some recent cross-currents of thought between anthropology and geography, and this is where the spatial anthropology side of the equation will hopefully begin to make a bit more sense.

Given that we’ve evoked the spirit of Frazer for this event, I feel duty bound to begin with at least some brief reflections on his legacy, to the extent that there is a legacy to speak of that is. My initial inclinations were to give him pretty short shrift. After all, as well as being an exponent of Darwinian evolutionist approaches to the culture and belief systems of so-called primitive cultures, Frazer was also famously known as an ‘armchair anthropologist’. Before the arrival of pioneers such as Malinowski or, in the United States, Franz Boas, Frazer’s generation rarely consummated the formative anthropological rite of passage that is fieldwork. For Frazer travel was limited to the vicarious kind, his analysis drawn from the expansive Orientalist literature that, in his day, passed for anthropological knowledge, and which, as Edward Said argued, played an key role in processes of European colonial expansion. In terms of Frazer’s legacy, his place in the canon of key anthropological writings taught at universities is for the most part likely to be marginal to the point of non-existence. Out of curiosity, in preparing this talk I dusted off my 1st year undergraduate lecture notes (in the mid 1990s I studied social anthropology at SOAS in London). I was not surprised to learn that The Golden Bough was not on any of the key reading lists, nor did it appear on any of the supplementary reading lists either. This appeared to confirm my suspicions that Frazer was nothing more than a footnote in the history of anthropology and that it wasn’t until Malinowski came on the scene that anthropology ‘proper’ – that is, something that more closely resembles what we might recognise as the discipline today – first began to take shape.

However, just as I was about to swipe Frazer and his legacy into oblivion, I realised that I had only recently drawn on his work myself in a paper on marketing popular music tourism sites, and that, footnote or not, his work still obviously has retained some degree of critical resonance. The paper in question took Frazer’s theory of contagious and sympathetic magic and argued the case that modern marketing discourses – particularly those that draw on the symbolic value associated with sites of local cultural heritage – often practice forms of what can be described as contagious magic. I won’t go into too much detail of the argument here (and refer you instead to the paper itself), but in a nutshell the idea being examined was the efficacy ascribed to the anticipated ‘rubbing off’ of cultural capital, as if, through contact or mimesis, some sort of economic and regenerative ‘magic’ will inevitably rub off and cast its benign spell over a city or region. Which is all well and interesting but need not concern us here. In terms of the current discussion, the point I wish to make here is that Frazer’s ideas (or some at least) have gone to inform later theoretical writings on magic and mimesis, whether this be the work of Walter Benjamin, or that of anthropologists such as Michael Taussig or Alfred Gell. Although my use of Frazer in this example probably more closely resembles what the Situationists refer to as an act of détournement than an acknowledged anthropological debt, it is nevertheless the case that Frazer’s book is still being referenced and ideas still being chewed over so there is undoubtedly a legacy there to speak of, albeit one that has been re-processed through subsequent and more substantive theoretical frameworks.

A description of anthropology I have always liked is one offered by Tim Ingold, which is simply ‘philosophy with the people in’. If we apply this to Frazer we immediately see the glaring anthropological deficit at the core of his enterprise: i.e. the conspicuous lack of actual human engagement and ethnographic interaction. It is philosophy without the people in. And before this begins to sound like a valorisation of the ethnographically-savvy Malinowski at the expense of the stay-at-home Frazer, it is worth paying brief mention to the controversy following the posthumous publication of Malinowski’s field diary in the late 1960s. Described by some as functioning as a kind of ‘safety valve’, the diary reveals racist and at times hostile attitudes towards his Trobriand informants which provide an altogether different view from that portrayed in his monograph, Argonauts of the Western Pacific. One of the more infamous lines from the diary is ‘on the whole my feelings toward the natives are decidedly tending to “Exterminate the brutes”’. With the phrase ‘exterminate the brutes’, Malinowski is directly quoting from fellow Pole Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness, not exactly a model of enlightened and empathetic ethnographic practice. That said, the ‘horror’ of some fieldwork experiences, if we can put it in those terms, would probably make for a fruitful area of discussion, and who knows, might even render Malinowski in a more sympathetic light insofar as the ethnographer-informant relationship is recognised as having its more testing moments. How many anthropologists, I wonder, in private moments of discomfort or despair have on occasion not harboured some less than wholesome views towards those they are studying? Anthropologists are only human after all. So coming back to Ingold’s ‘philosophy with the people in’, the point I wish to raise here is that, however distasteful, the diary provides valuable insights into Malinowski the man, rather than Malinowski the scientifically objective anthropologist, the latter being of course a complete fiction. These more ‘back stage’ reflections allow for a greater recognition of the situated, subjective and in many ways contingent realities that are framed by the ethnographic encounter. So in pragmatic terms at least, the idea of ‘philosophy – or anthropology – with the people in’ highlights the importance of critically taking on board questions of reflexivity, the value and role of personal narratives and experiences, and of considering how adopting more auto-ethnographic methods of fieldwork practice might be useful or productive.

A useful example to consider here is Marc Augé’s much-cited book Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. I very clearly remember when I was first introduced to this text, which was in a lecture in my first year at SOAS. The lecturer held up the slim volume in one hand and in the other he brandished the weighty tome that is Manuell Castell’s The Rise of the Network Society, which had also just been published. The lecturer’s point wasn’t to necessarily argue the merits for one over the other – for Augé vs Castells – but rather to highlight the uniquely anthropological perspective on offer in Non-Places, and to show the value of auto-ethnographic narratives in fleshing out the lived spaces of what Augé calls ‘supermodernity’. These are spaces of transit such as airports, high speed road networks, shopping malls, etc. and which represent the architectural and geographical counterpart to Castell’s ‘space of flows’. What Augé was also doing in the book was to highlight the challenge of relating some of the established anthropological ideas of place and space – such as those from a more Durkheimian tradition – to these new ‘placeless’ or transitory environments. In the book Augé doesn’t really develop as full or as adequate response to this challenge himself, the book offers more of a diagnosis than a fully-fledged ethnographic study of these landscapes. However, that said, the publication of Non-places was without doubt an important intervention in the development of specifically anthropological approaches to place and space – or ‘spatial anthropology’ if you prefer.

Another influential book that left its mark on my early adventures in anthropology was Michael Jackson’s Paths Toward a Clearing: Radical Empiricism and Ethnographic Inquiry, published in 1989. As an undergraduate I remember being very excited by this discovery and could not understand why this strand of anthropological theory and method was not more widely practised. Jackson’s work is very much rooted in an American tradition of cultural anthropology as opposed to the Durkheimian structural-functionalist tradition that has shaped the development of much Anglo-French social anthropology. As a leading exponent of phenomenological and existential anthropology, Jackson’s work explores questions of experience, embodiment, and the senses, and he offers a fieldwork model which places the anthropologist full square in the immersive field and experiential flux of the ethnographic encounter. This is what is meant by a ‘radical empiricist’ ethnographic method, drawing on everything that the field throws at you, whether emotional, bodily, sensory, performative, spatial, intersubjective, observational, thick description and so on. Strongly influenced by, amongst others, the pragmatist philosophy of William James, the phenomenological writings of Heidegger, Sartre and Merleau Ponty, as well as the work of Pierre Bourdieu, Jackson’s brand of anthropology, which is mostly based on his work with the Kuranko peoples of Sierra Leone, offers a rich embracing of Ingold’s ‘philosophy with the people in’ prescription. The core focus on experience also has close affinities with the work of experiential anthropologists such as Victor Turner and Ed Bruner.

Another phenomenological anthropologist we could briefly mention here is Thomas Csordas, whose work sits mainly in the area of medical and psychological anthropology and theories of embodiment. Commenting on the methodological focus on issues of affect, emotions, embodiment, performance and the senses, Csordas is keen to stress that ‘it will not do to identify what we are getting at with a negative term, as something non-representational’ (1994: 10). In other words, just because phenomena cannot be ‘represented’ in conventional empirical observational terms, it doesn’t make it ‘non-representational’ (and this takes us back to the radical empiricism championed by figures such as Jackson). If we jump back to Augé for a second we can get a sense of the shortfalls of Augé’s answer to his own question of how do you conduct an anthropology of supermodernity? How do you begin to go about ethnographically investigating a space such as an airport terminal? The shortfall in Augé’s approach is perhaps on account of his being hamstrung by a rigid dualism of representational vs. non-representational thinking. And that this is in part a reflection of a disjuncture between anthropology modelled on a structural-functional intellectual heritage (of which Augé is clearly an inheritor), and one more reflective of the interpretative, experiential and phenomenological approaches exemplified by anthropologists such as Jackson and Csordas.

When we start to examine this from a wider cross or post-disciplinary context the marginalisation – certainly in British schools of social anthropology – of more phenomenological approaches to anthropological fieldwork has opened the way for scholars from other disciplinary backgrounds to steal a march, effectively. And this, I am suggesting, has possible negative ramifications in terms of the longer term sustainability of anthropology in British universities, where it sometimes seems as though it is clinging on by its fingertips. When we consider the sort of approaches pioneered by US anthropologists such as Jackson alongside initiatives that have been developed in other disciplines, most notably in geography, we can get a sense of how many of these ideas have diffused across disciplines. To take this slightly further, and proceeding from Csordas’s well observed note of caution about the term ‘non representational’, it is worth briefly considering ideas around so-called ‘non representational geographies’.

I am not going to go into this in any great depth, and I’m working towards a conclusion anyway, but I just wanted to consider some of the claims made with regard to non-representational theory. And these are cited with the preceding discussion very much in mind. I am quoting here from Nigel Thrifts 2007 book Non-Representational Theory: Space, Politics, Affect.

Acknowledging the ‘increasingly diverse character’ of non representational theory, and that ‘it has a lot of forebears’, Thrift outlines some of its key tenets:

· — the importance of ‘radical empiricist’ epistemologies;

· — the ‘on-flow’ and flux of everyday life;

· — the ‘spillage of things’ (the material and technological apparatus of everyday social being – our relationship with objects and non-human agents);

· — corporeality, affect, and the senses;

· — performance and play;

· — and an attentiveness to practices, ‘understood as material bodies of work or styles that have gained enough stability over time, through, for example, the establishment of corporeal routines’ .

Another introductory or sound-bite definition Thrift offers is that non representational theory is about ‘the geography of what happens… what is present in experience’ (ibid: 2, emphasis in original). ‘The geography of what happens’ is certainly an intriguing turn of phrase. In our paper ‘(Un)Doing Tourism Anthropology’, Hazel Andrews and I float the contention that ‘the geography of what happens’ can almost be looked upon as an attempt to dress anthropological issues of place, practice and performance in the clothes of the geographical. Given that everything that happens happens somewhere (and that all anthropological phenomena is, therefore, at least partly if not intrinsically geographical) then where does this leave the anthropologist? And where does it leave anthropology as a discipline? If, rather than thinking about it in disciplinary terms, we think about anthropology in terms of its ‘doing-ness’ – in other words, in terms of its application as a wider field of practice – then what the example of non-representational geography helps us illustrate is that what might count as doing anthropology is not necessarily conditional on there being an explicitly framed discipline that is recognised in terms of it being anthropology. In other words, you don’t necessarily have to be an anthropologist to do anthropology.

If this is the case (and I am not claiming that it is necessarily), but if it is then it is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, the uptake of ethnographic methods that have been at the core of anthropological thinking and practice for decades are given a further reaching lease of life through different channels of theory and practice. At the same time it poses questions as to the specificity of anthropological perspectives and critical orientations (and the knock-on effects this might have for anthropology departments). Paul Gilroy has talked of the process of ‘filleting’ that sometimes occurs when ideas and theories translate between disciplines (particularly in the case of social science theories imported into business and marketing models). So for those of us who would wish keep faith in terms of ascribing to the idea of ‘philosophy with the people in’ rather than, say, a more nebulous ‘geography of what happens’, then it seems to me the task of practicing anthropology – whatever the disciplinary or institutional setting – demands a certain degree of vigilance and, for want of a better term, ‘anthropological advocacy’.

If, for the purposes of a few closing remarks, you can once again forgive the indulgence of my relating these points of consideration to my own experience, then the at times convoluted passage through three major interdisciplinary projects is one that has, if anything, re-affirmed my own convictions of the value of identifying more closely with this idea of anthropology as a field of practice. As a postdoctoral researcher I worked on two consecutive projects on film, mapping and urban space, and a European collaborative project on popular music, heritage and cultural memory. As interdisciplinary research programmes (working collaboratively with architects, geographers, sociologists, cartographers, film scholars, popular music scholars and others) all of these projects presented certain challenges in terms of negotiating a passage through a number of what were, at times, competing trajectories and perspectives. It is perhaps only in hindsight and on account of a closer rapprochement with anthropological approaches that it occurs to me that what probably underpins all the points of negotiation that made the projects so interesting to work on is some degree of adherence, on my part, to the principle of ‘philosophy with the people in’, or at least to skew things back towards more of an anthropological perspective. To conclude with a rather woolly call for a focus on ‘people’ sounds a bit trite, I know. But it is surprising how often you find yourself having to re-affirm – as much as to yourself as those around you – this otherwise quite elemental point of principle. Taken alongside the fact that, to paraphrase Henri Lefebvre, people have a social existence to the extent that they also have a spatial existence, it is also to re-affirm the idea of ‘geography with the people in’ (or indeed ‘architecture with the people in’). Whether ‘geography with the people in’ is the same thing as ‘human geography’ or not is probably one of those heads of a pin questions and not best pursued, but ‘spatial anthropology’, for my money at least, is a term that sits more comfortably as part of a wider, post-disciplinary field of practice.

References

Augé, M. 1995. Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. London: Verso.

Castells, M. 1996. The Rise of the Network Society. The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture Volume 1. Oxford: Blackwell.

Csordas, T.J. 1994. ‘Introduction: the Body as Representation and Being-in-the-world’, in T.J. Csordas (ed.),1994. Embodiment and Experience: The Existential Ground of Culture and Self. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Frazer, JG. 1924. The Golden Bough. London: Macmillan.

Ingold, T. 1992. ‘Editorial’, Man N.S. 27(4): 693–96.

Jackson, M. 1989. Paths Toward a Clearing: Radical Empiricism and Ethnographic Inquiry. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Thrift, N. 2007. Non-Representational Theory: Space, Politics, Affect. London: Routledge.

Roberts, L. 2014. ‘Marketing Musicscapes, or, the Political Economy of Contagious Magic’, in Tourist Studies, 14 (1).

Roberts, L. and H. Andrews. 2014. ‘(Un)Doing Tourism Anthropology: Outline of a Field of Practice’, Journal of Tourism Challenges and Trends.

Smith, M.1999. ‘On the state of cultural studies: an interview with Paul Gilroy’, Third Text, 13 (49): 15-26.

Les Roberts, 13 November 2013.

I visited the University of Liverpool in London campus for the first time this week. I remember when the building it occupies was the Bank of Nova Scotia. This was back in the 1990s when I was working in the area for a period (the bus stopped right outside). The building still has the feel and corporate ambience of an investment bank, which I suppose seems appropriate given the ‘trading’ of knowledge that is now expected to take place in the brave new marketised world of the neoliberal university.

I visited the University of Liverpool in London campus for the first time this week. I remember when the building it occupies was the Bank of Nova Scotia. This was back in the 1990s when I was working in the area for a period (the bus stopped right outside). The building still has the feel and corporate ambience of an investment bank, which I suppose seems appropriate given the ‘trading’ of knowledge that is now expected to take place in the brave new marketised world of the neoliberal university.

Arrived back last night from this year’s

Arrived back last night from this year’s  I-Media-Cities Conference Brussels

I-Media-Cities Conference Brussels On 22 May I presented a paper at a symposium held at LJMU, organised by Yannis Tzioumakis (University of Liverpool) and Lydia Papadimitriou (LJMU) –

On 22 May I presented a paper at a symposium held at LJMU, organised by Yannis Tzioumakis (University of Liverpool) and Lydia Papadimitriou (LJMU) –  This Liqufruta bottle is a found object which was my contribution to a workshop organised by Hazel Andrews and held at the Royal Anthropological Institute, London on Thursday 13th March 2014.

This Liqufruta bottle is a found object which was my contribution to a workshop organised by Hazel Andrews and held at the Royal Anthropological Institute, London on Thursday 13th March 2014. [Below is the publicity blurb for an event I took part in at UCLAN this week…]

[Below is the publicity blurb for an event I took part in at UCLAN this week…]

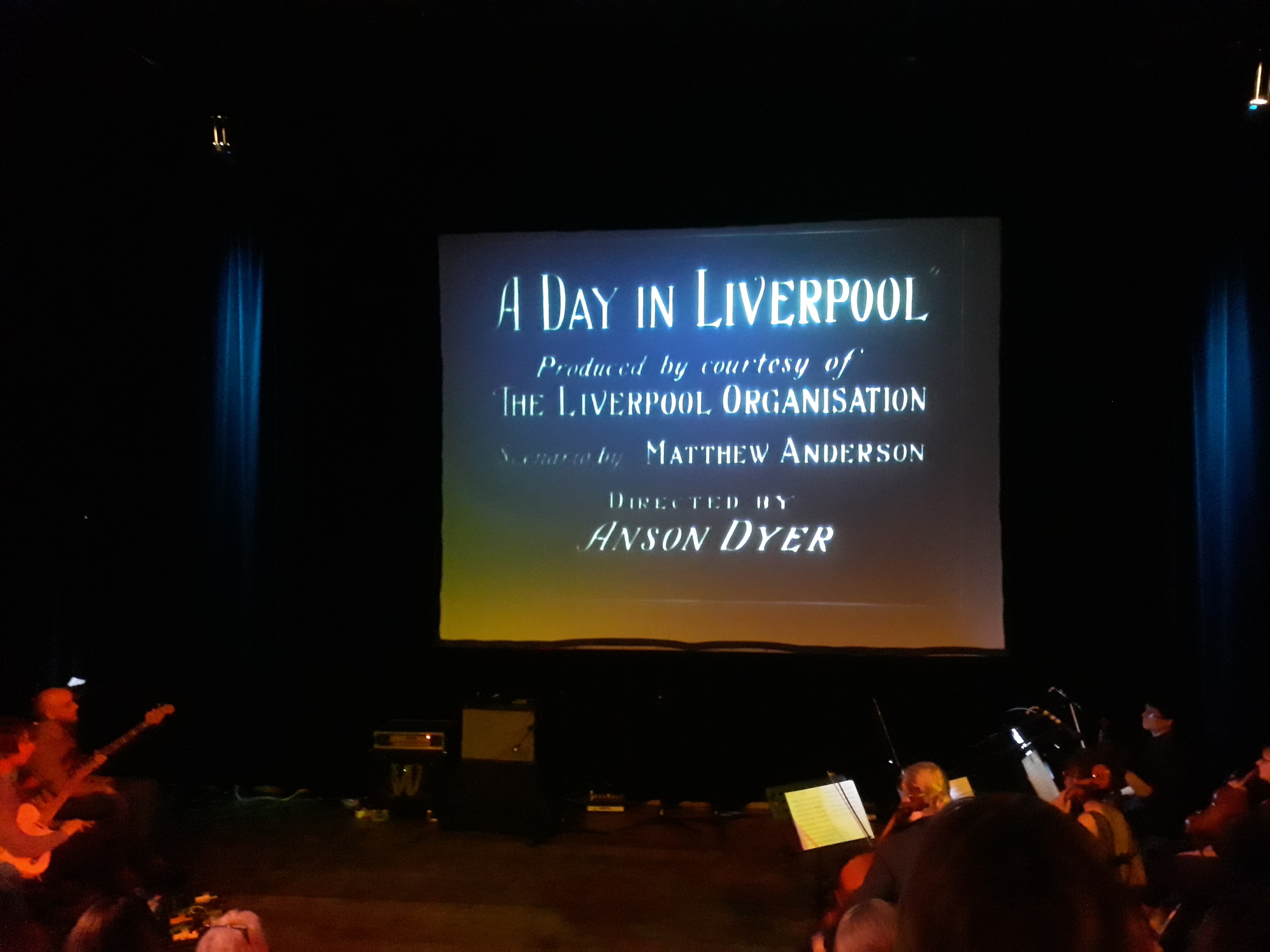

I was invited to present at an event organised by Liz Stewart from the Museum of Liverpool on behalf of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire. The event, ‘Getting There: Exploring the History of North West’s Transport Links’, was held at the Museum on 18th September 2013. My talk was called ‘Making Connections: Amateur Transport Films and Merseyside’s Historical Geography’. Other speakers included Sharon Brown from the Museum of Liverpool, Richard Knowles, Professor of Transport Geography at the University of Salford, and Martin Dodge, Senior Lecturer in Human Geography at the University of Manchester.

I was invited to present at an event organised by Liz Stewart from the Museum of Liverpool on behalf of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire. The event, ‘Getting There: Exploring the History of North West’s Transport Links’, was held at the Museum on 18th September 2013. My talk was called ‘Making Connections: Amateur Transport Films and Merseyside’s Historical Geography’. Other speakers included Sharon Brown from the Museum of Liverpool, Richard Knowles, Professor of Transport Geography at the University of Salford, and Martin Dodge, Senior Lecturer in Human Geography at the University of Manchester. Invited to give a talk at the ‘Placing Morecambe’ symposium organised by David Cooper and Jo Carruthers and held at the Dept. of English and Creative Writing at Lancaster University on 13 June 2013. This event followed on from the ‘Practising Morecambe’ field excursion and group exercise on 30 May (which for me also involved a night in the legendary Midland Hotel, replete with endless piped 1930s dance music – eerily reminiscent of the barroom music from The Shining). In my presentation I discussed some ideas relating to spatial anthropology and the relationship between the critical and the creative. I also provided some reflections on the creative process and outputs developed from the Morecambe field exercise, including a slide show of images gleaned from my walks around the town, and a poem, ‘Frontierland’, inspired by the practice of ‘placing Morecambe’.

Invited to give a talk at the ‘Placing Morecambe’ symposium organised by David Cooper and Jo Carruthers and held at the Dept. of English and Creative Writing at Lancaster University on 13 June 2013. This event followed on from the ‘Practising Morecambe’ field excursion and group exercise on 30 May (which for me also involved a night in the legendary Midland Hotel, replete with endless piped 1930s dance music – eerily reminiscent of the barroom music from The Shining). In my presentation I discussed some ideas relating to spatial anthropology and the relationship between the critical and the creative. I also provided some reflections on the creative process and outputs developed from the Morecambe field exercise, including a slide show of images gleaned from my walks around the town, and a poem, ‘Frontierland’, inspired by the practice of ‘placing Morecambe’.