On Saturday 14 September I attended a screening of two archive film projects that were performed with a live score at the Bluecoat in Liverpool. www.thebluecoat.org.uk/events/view/events/4036

The first, Tracks by the composer Luke Moore, featured footage shot of and from the Liverpool Overhead Railway that included the first ever moving images of Liverpool, filmed by the Lumière cameraman Alexander Promio. The film also included some stunning 3D animation of the railway and surrounding urban landscape by the artist Steven Wheeler (www.stevenpaulwheeler.com/).

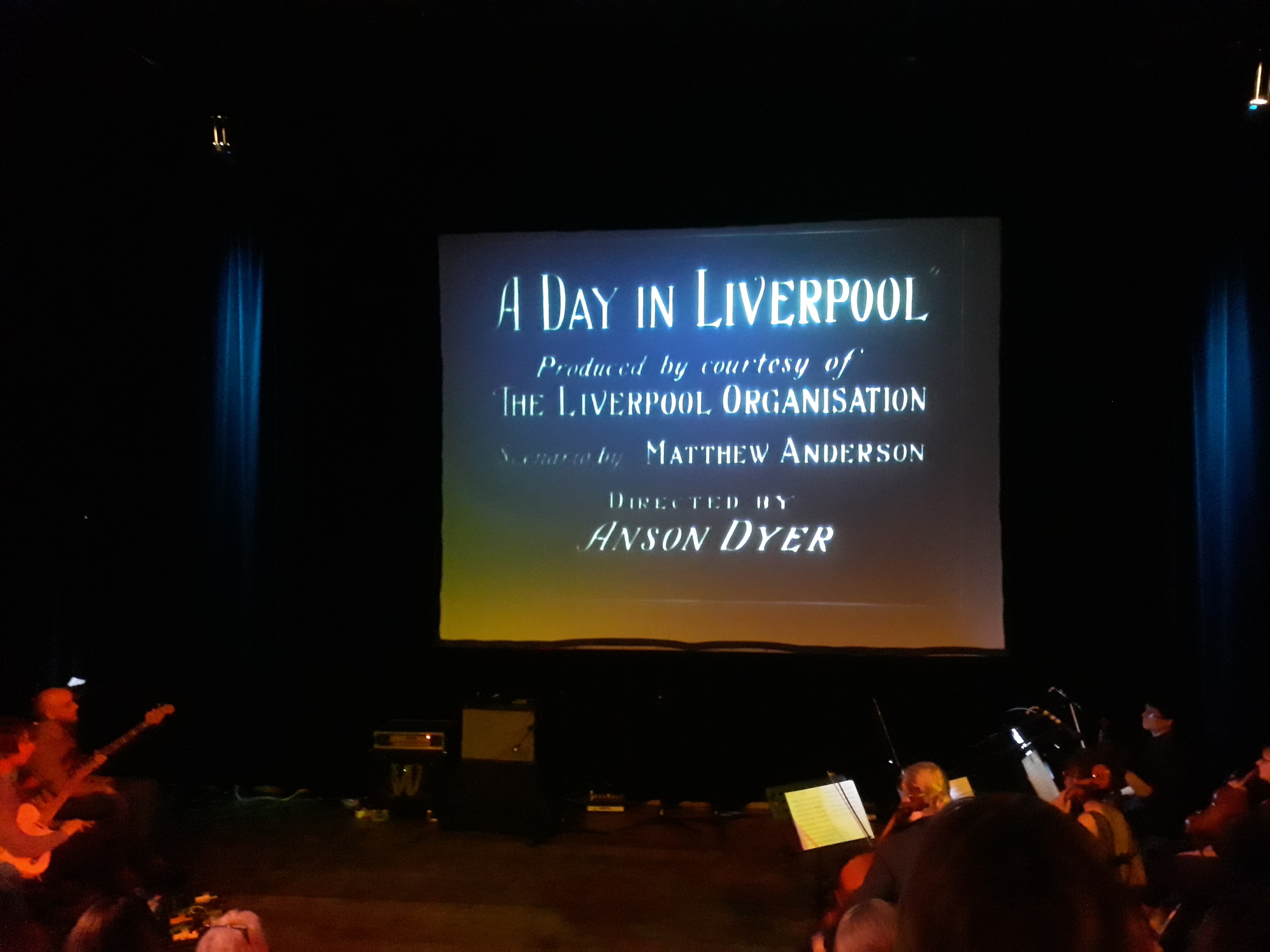

The main feature, Anson Dyer’s 1929 ‘city symphony’, A Day in Liverpool, was screened with a live score performed by composer and songwriter Aidan Smith. I had seen this film many times before, but seeing it for the first time, on a big screen, with a much-needed score transformed the film and brought it alive in ways that a mute viewing on a laptop simply cannot match.

I was invited by Anselm Burke to take part in a post-screening discussion along with Luke, Steven, and Aidan. Interesting chat afterwards with people sharing their memories of the Overhead Railway.

Below is a short piece about A Day in Liverpool that I was asked to write by way of background to the film for those attending:

A Day in Liverpool

As a ‘city symphony’, although it is not quite in the same league as such classics as A Man With a Movie Camera (Dziga Vertov, USSR, 1929), A Day in Liverpool undoubtedly qualifies inasmuch as it showcases some of the genre’s key features and motifs. Like Man With a Movie Camera (which, not coincidentally, was also made in 1929), A Day in Liverpool goes out of its way to give a sense of the city’s rhythms as orchestrated by the director and editor (or should this be ‘conductor’?). It does this by drawing on the dynamism and seemingly inexhaustible energy of a city at work (and, to a lesser extent, at play). Structured around the working day, the film ebbs and flows with the activities of office workers (their hurried footsteps streaming up the steps of the Port of Liverpool Building), dock workers, merchants, traders, construction workers, commuters, shoppers, street hawkers, leisure-seekers and others caught up with, and contributing to, the rhythms of everyday life in what was a bustling, frenetic and above all industrious city. What the film also depicts in all its soot-choked splendour is the Liverpool Overhead Railway (LOR), known affectionately as the ‘Dockers’ Umbrella’ in tribute to the lively urban scenes that unfold beneath as much as along the elevated sections of track. One particular shot of the LOR, filmed from the top of the Liver Building, offers what is nothing short of an iconic view of Liverpool’s urban landscape as it was in the late 1920s, a gloriously cinematic cityscape which would not look out of place in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, made two years earlier in 1927. If these images seem familiar, this is on account of their appearance in Terence Davies’s celebrated documentary or ‘cine-poem’ from 2008, Of Time and the City (although it should be noted that the images are historically out of sync with the diegetic time-line of Davies’ film, which covers the years from the director’s birth in 1945 to his eventual departure from Liverpool in the 1970s). Footage from A Day in Liverpool also appears in a documentary produced by British Pathé in 1957, called This in Our Time (now available for purchase on DVD). A film that has been little seen in a theatrical setting, and which has only ever existed in mute or silent form, A Day in Liverpool is itself deserving of a wider audience and commercial DVD release. And if there ever was a film from Liverpool’s rich archival film heritage that has been crying out for a much needed score, then A Day in Liverpool, the city’s first and only city symphony, is most certainly it.

Les Roberts, September 2019